At some point in the last 10 years, you’ve probably wondered if there will ever be a day when you can upload your brain to the Internet. Now you can thanks to our ability to organize knowledge in networks.

Networked thought: an inflection point in the “total-recall” revolution

In his book, Total Recall, Microsoft researcher and author Gordon Bell gave us a glimpse of what it would look like if you could upload your brain to the Internet. Bell’s biggest challenge was the ability to organize and recall knowledge without friction, as he describes in his follow-up book:

But even with all my documents and pictures stashed away in a well-thought-out classification hierarchy of file folders, it was hard to find particular items quickly, if at all, because it required remembering where it was put. It was just like a library organized by subject without a card catalog. Poring through multiple folders for the right name or thumbnail icon took too much time.

Thanks to networked thinking, we have reached a turning point in the “total recall” revolution.

- It takes far less effort to upload your brain to the Internet than it did when Bell launched his MyLife Bits project.

- In a self-organizing workspace like Mem, you can find exactly what you need, when you need it, without having to remember where you saved it, how you tagged it, or the title you gave it.

- Since all your Mems are nodes in a network, not notes in a database, your ability to retrieve knowledge becomes more frictionless with each node you add to the network.

Networked thinking is not just a more efficient way to organize information. It frees your brain to do what it does best: Imagine, invent, innovate, and create.

The less you have to remember where information is, the more you can use it to summarize that information and turn knowledge into action.

Why This Matters to Me

Over the past 13 years, I’ve interviewed 1000 people, read 1000 books, written 4, and published 100 articles online. The amount of information I’ve both consumed and produced has made my brain feel like a disorganized encyclopedia, full of information that would be useful if I could access it.

- As I like to say, if you want to rob a bank, become a porn star, or run for president, I can introduce you to the people who can help you.

- On several occasions, I’ve jokingly told friends that if I could implement all the advice I’ve received, I’d be a billionaire with a six-pack and a harem of supermodels. Alas, I’m none of those things.

- When I asked neuroscientist Tara Swart what the inside of my brain looked like after 1,000 interviews, she said, “Your brain is the kind of brain we want access to when we can upload our consciousness to the Internet.”

Regardless of whether others want to access my brain or not, I want to be able to access and use my knowledge.

Thanks to networked thinking, today you can upload your brain to the Internet by building a second brain that functions with remarkable similarity to your real brain. But first, you need to understand how information is organized in your brain.

How Information is Organized In Your Brain

The mind has a trace of every experience you’ve ever had. There are traces of every piece of information you were exposed to, every thought that went through your mind, every emotion you felt, and every experience you had.

Your Brain is a Network, Not a Hierarchy

Your brain isn’t like a hard drive or a dropbox, where information is stored in folders and subfolders. None of our thoughts or ideas exist in isolation. Information is organized in a series of non-linear associative networks in the brain.

Memory, at the most fundamental physiological level, is a pattern of connections between those neurons. Every sensation remembered, every thought that we think, transforms our brains and the connections within that vast network. By the time you to the end of this sentence, your brain will have physically changed – Joshua Foerr, Moonwalking with Einstein

For example, when you think of one of your favorite songs. Since memory is contextual, when we recall a memory, we recall all the memories associated with it without friction. The song, the memory, and the emotion are all nodes in an information network in your brain.

How Your Brain Encodes Major Life Events

Important life events encode deeper memories. You probably remember in detail your wedding day and the birth of your first child. But if you pick any day from that year, you probably will not remember much. The nodes for your most important life events are larger and therefore more deeply encoded.

In my interview with Daniel Levitin, I asked him why music affects our memory the way it does.

- For the last game of our 7th grade basketball season, the coach had us take the court like an NBA team. When we entered the gym, the Van Halen song Jump was playing. Every time I hear that song, I remember that game.

- My brain made a connection between the conversation I was having with Daniel and an experience I had 25 years ago.

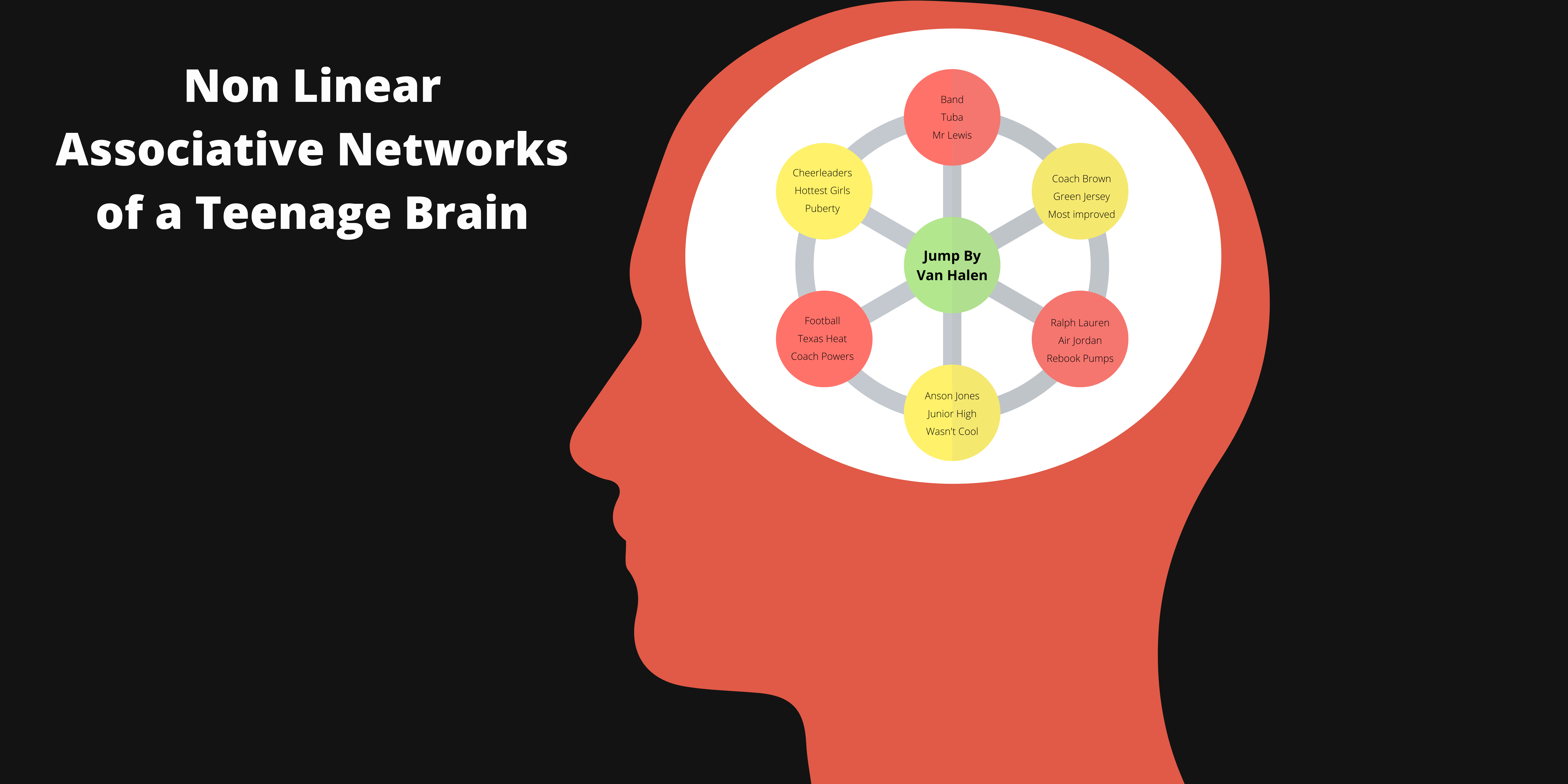

- Writing this article also triggered dozens of other memories I associate with 7th grade, as you can see in the diagram below – which clearly points to the fact that I was a teenager with raging hormones.

Every single word in this diagram is another node with thousands of other nodes connected to it.

Part 2: Why Organizing Knowledge in Networks Feels Counterintuitive

Although the brain is a network and not a hierarchy, people struggle with networked thinking because we’ve been conditioned all our lives to think linearly and to use linear organizational systems for non-linear processes.

How we’re conditioned to think linearly.

The path from kindergarten to high school graduation is linear. And for many people, so is the path from high school to college.

- In the real world, you find that life is not linear. It rarely goes according to plan. Talk to someone who’s in their 40s, and their life looks different than they thought it would when they were 20.

- We are taught to write 5-paragraph essays by creating an outline with a hypothesis, three supporting paragraphs, and a conclusion. But any writer who has ever written a book will tell you that’s not what the process looks like. The structure may be linear, but the process of writing a book is not.

- The user interface of most note-taking apps forces people to think linearly and organize information in the same way. Ironically, most of these apps are not designed to work the way the human brain does.

You are probably wondering what this has to do with organizing your knowledge in networks. Social conditioning leads us to believe that everything is linear.

That’s why people feel so overwhelmed and confused when they first start using apps like Mem, wondering, “How do I organize information in this thing?” But they’re overlooking something that’s hard to grasp because they’ve been conditioned to think linearly.

Networks give you the freedom to take notes, capture ideas as they occur, and organize information as you think. But the power and value of an app like Mem aren’t obvious because there’s something I call the utility paradox.

The Utility Paradox

With new technologies, it’s hard to understand why something is useful until you’ve used it yourself. Think about how many products seemed useless, crazy, or downright stupid when people first invented them.

Some investors thought Airbnb and Uber sounded like murder movies in the making. But today, no one questions using Uber for transportation or Airbnb for lodging. Ideas that sound dumb when they’re conceived become our new defaults

Twitter’s Utility Paradox

When I discovered Twitter, I thought it was one of the dumbest ideas in the world.

- The user interface isn’t intuitive, so it felt useless.

When a new technology is adopted by users, people use it in ways the founders can’t envision when people think their ideas are crazy or stupid.

- Jack Dorsey probably never imagined that people would one day use Twitter to overthrow dictatorships and that presidential candidates would use it to divide a country’s citizens.”

- Through Twitter, I met my most influential mentor and hundreds of podcast guests.

Until you resolve the utility paradox, you fall into the trap of functional fixedness, meaning you only see one way to use a new tool. The same is true for a tool like Mem. As you capture your tasks, insights, thoughts, and ideas in Mem, your ability to use them evolves.

As Futurist Jane Mcgonical says, “The ubiquity of the words “unthinkable” and “unimaginable” in our stories tells us something important about our global condition. We feel blindsided by reality. We find ourselves struggling to make sense of events that shattered our assumptions and challenged our beliefs.”

Networked thought challenges our assumptions about linear thinking.

Part 2: Upload Your Brain to the Internet by Building a Personal Network of Knowledge

You already upload your brain to the Internet, but the parts you’ve uploaded belong to someone else and are being exploited by them.

Whether we realize it or not, we’ve been uploading our brains to the Internet for decades. But companies like Facebook, Google, and Instagram are the main beneficiaries of the parts of our brains that we’ve uploaded to the Internet.

- Every status update you write, every tweet you compose, and every image you upload starts as a thought in your brain that you transfer to a social network for other people to consume and for companies to sell your data and attention to advertisers. To access the parts of your brain that you uploaded to a social platform, you’ve to go back to the social network where they live.

- Every time you go back to access knowledge or information you want on Facebook, you spend more time on Facebook. Facebook makes money for every second you spend on its platform. And you’ll probably end up down a rabbit hole chasing shiny objects.

- When you send emails, enter appointments into a digital calendar, or enter tasks into a task management tool, you’re uploading your brain to the Internet.

By contrast, when you organize YOUR knowledge in a network, you aggregate the flow of information and upload YOUR brain to the internet

Step 1: Build a Personal Network of Knowledge

I imagine for a moment that you could plug your brain into your computer with a USB cable and upload the contents to a folder. Since this is not the way information is organized in your brain, it would be useless. And it would take a lot of cognitive effort to organize, retrieve, and use what you uploaded.

The only way to upload your brain to the Internet so that you can retrieve and use knowledge without friction is to build a Personal network of knowledge.

In a personal network of knowledge every note, idea, thought, and insight is a single node connected to all other nodes. You connect individual nodes with bidirectional links and groups of nodes with tags. This way, every time you capture a new note, you can make a connection between what you learn and what you know.

Networks are More Efficient Than Hierarchies

“Research from Microsoft shows that the average US employee spends 76 hours per year looking for misplaced notes, items, or files. And a report from the International Data Corporation found that 26 percent of a typical knowledge worker’s day is spent looking for and consolidating information spread across a variety of systems. Incredibly, only 56 percent of the time are they able to find the information required to do their jobs” says Tiago Forte in his book, Building a Second Brain.

The way we organize information is the main cause of inefficient knowledge work, which becomes clear when comparing the hyperactive hivemind workflow with the networked workflow.

The hyperactive Hivemind Workflow

Let’s look at managing a project with the hyperactive hivemind workflow.

- Communicating with collaborators via email and instant messaging

- Retrieving important resources by browsing bookmarks, folders, and inboxes

- Managing tasks in a project management tool

The hyperactive Hivemind workflow forces you to multitask and context shift. To make matters worse, context shifts increase attention lag, which decreases your productivity and effectiveness. The hyperactive hivemind is the equivalent of buying every ingredient for a peanut butter and jelly sandwich at a different grocery store and turning five-minute tasks into fifty-minute tasks.

The time we waste searching for information leads to what Cal Newport calls the “hyperactive hive.”

A workflow focused on constant conversations fueled by unstructured and unscheduled messages via digital communication tools like email and instant messenger services.

The Networked Workflow

Now let’s look at managing the same project with a networked workflow. As you Aggregate the flow of information into a personal network of knowledge, you can complete all project-related tasks within it.

- Communicate with your collaborators

- Store, access, and use your knowledge at ONE.

- Find exactly what you need, when you need it

- Give employees access to resources Knowledge assets on the network

In summary, organizing information in networks is the antidote to the hyperactive hivemind

Step 2: Build a Digital Search Engine for Your Brain

Search engines like Google allow you to search the collective brain of humanity uploaded to the Internet.

- The validity of an academic text is measured by the number of citations in other publications.

- Google’s page rank algorithm works the same way.

- The authority of a website is based on the number of websites that link to it.

- Websites that have the most backlinks are at the top of the search results.

When you upload your brain to the Internet, you need to be able to search your Personal network of knowledge the same way you would search for information on Google. To do this, your knowledge must be externalized, discoverable, and networked.

- Externalization makes your knowledge accessible

- Distillation makes your knowledge discoverable

- Interconnectedness makes your knowledge connectable

Retrieving your knowledge must be as easy as searching for information on Google. Networked knowledge is like a page rank for your brain Google’s job is to organize the world’s information. The job of someone who builds a knowledge network is to organize their own knowledge so that they can use it at will.

Part 4: How Networks Generate Knowledge

When you organize your knowledge into a network, you build nonlinear associative knowledge networks that not only store information but also generate additional knowledge.

Spontaneous Insight without immediate action

Valuable spontaneous ideas go to waste if you don’t capture them. But ideas take time to mature and rarely emerge in full form. On the day I wrote this, “write an article about how to upload your brain to the Internet” wasn’t on my to-do list. It just came to me while I was working on something else.

So I created a bidirectional link and captured that idea without interrupting my workflow. You don’t have to know how or when you’ll use something you capture, because knowledge organized in networks promotes insight and allows you to follow your curiosity until you reach a useful insight.

Spontaneous recall and Retrieval

When knowledge is buried in hierarchies such as folders and subfolders, you must make an active effort to remember where it is and retrieve it. However, when that knowledge is in a network, it always resurfaces.

One Idea Per Note is Enough

Even if you capture one idea per note, which may consist of one or three sentences, you create what Tiago Forte calls intermediate packages, “the concrete, individual building blocks that make up your work.” All your intermediate packets become knowledge-building blocks that make it easier to break ambitious goals into small manageable pieces.

Create at the speed of thought

Uploading your brain to the Internet and accumulating a wealth of knowledge creates a cycle of knowledge generation.

You have thousands of knowledge assets and knowledge building blocks (i.e., notes from books, ideas, paragraphs of key insights) that you can use to make connections between your ideas and transform elements of previous creations into new ones.

In a network, the utility of knowledge doesn’t expire. Every note thought, or idea you capture is a reusable knowledge asset. This entire article is the result of notes I took from books, other projects, and articles I never finished writing sometime in the last 18 months.

Can You Really Upload Your Brain to the Internet?

The answer is yes. But it Isn’t as simple as plugging a USB cable into your brain and importing it into a dropbox folder. It’s a bit more like an interesting-bearing bank account. With every note, idea, thought, and insight you capture, you add a new node that causes the collective value of the entire network to compound. And eventually, the Functions of Your Second Brain mimic the Functions of your First Brain.

Ready to Upload Your Brain to the Internet

Imagine the power you’d have at your disposal if you could capture EVERYTHING in one place, spend less time organizing and more time USING your knowledge. Check out our free course on how to take smart notes that will show you to stop collecting quotes and capture notes that you can use to remember what you read, generate ideas with ease and use your knowledge to create content, and move your projects forward faster than you ever thought possible. Click here to learn more